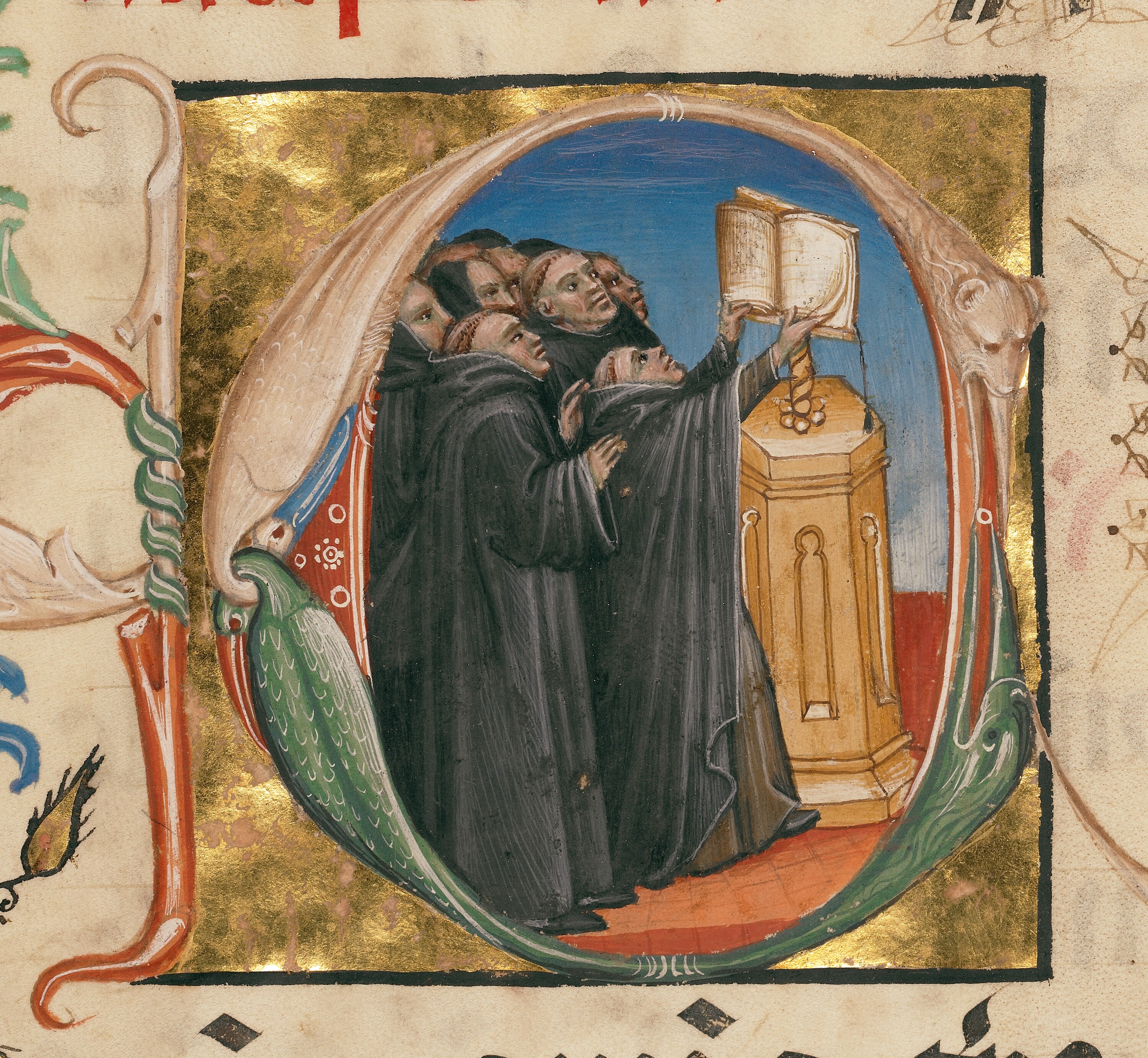

Benedictines

![]()

St. Gall, Ge

rmany

Religious, Christian

Celibate

825 AD

St. Gall, Ge

rmany

Religious, Christian

Celibate

825 AD

1 Hostel 2 Brewery / Baker 3 Guest House 4 School 5 Abbot’s House 6 Leeching 7 Physician 8 Herb Garden 9 Entrance 10 Church 11 Kitchen & Bath 12 Infirmary 13 Chapel 14 Novitiate 15 Barns 16 Almonry 17 Cellar 18 Dormitory 19 Orchard Cemetery 20 Stables 21 Cooper 22 Refectory 23 Bath 24 Garden 25 Chickens 26 Kiln 27 Press 28 Mill 29 Shops

The plan of St. Gall is the only major architectural drawing from the seven centuries between the fall of the Roman empire and 13th century. The ideal plan of a Benedictine monastery depicts a micro-urbanity, containing everything needed for a self-sufficient community of 110 monks and 170 laymen. The central role of religion is clear in the size and placement of the Church, whose pews seat exactly 112, but the layout also demonstrates an earthly pragmatism: chicken coops adjoin vegetable gardens so that scraps can be fed to the chickens and chicken droppings can be used as fertilizer (24, 25); the bakery and brewery, which both require an active yeast and temperatures above 75 degrees, shared a building kept warm by the bakery oven (2). Strict metrics of population and rationing are rendered in minute detail: the barrels of beer in the cellar (17), correspond to the (recommended) drinking needs of 300 monks and laymen. Vows of chastity were aided by the architecture, which affords little privacy in both the group dormitory and the baths which could only accommodate one at a time. The plan represents ta Utopia of Scarcity or a Utopia of Temperance. These classical Utopias are static and hierarchical due to a scarcity of resources. It doesn’t grow, it sustains itself. It produces exactly what it needs to do this including moral behavior. The plan of St. Gall, as a shorthand for most cloisters and monasteries, is isolated, self-sustaining, and pragmatic.

St. Gall End Notes

Horn, Walter, Ernest Born, Wolfgang Braunfels, Charles W. Jones, and A. Hunter. The Plan of St. Gall: A Study of the Architecture & Economy of, & Life in a Paradigmatic Carolingian Monastery. University of California Press, 1979.

“Heaven on Earth: The Plan of St. Gall.” The Wilson Quarterly (1976-) 4, no. 1 (1980): 171–79. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40255780. Page 175.